The trick to a good exhibition of art, history or indeed anything is not just in the choice of artefacts. There’s a real art to laying it out. It has to be done in a way that takes the visitor on a journey, that turns the collection into a story. While ‘Cook and the Pacific,’ currently on at the National Library of Australia, is expertly laid out, it manages to encapsulate a lot of what it does right in the entryway.

You’re greeted by a selection of first nations representatives, greeting you in their native tongues, and shown a huge, blown up picture of a small woodcut of the Captain. It manages to encompass how he has been blown up into a legend and how the exhibit wants to zoom in on every aspect of his story, especially the aspects of the story that were often forgotten.

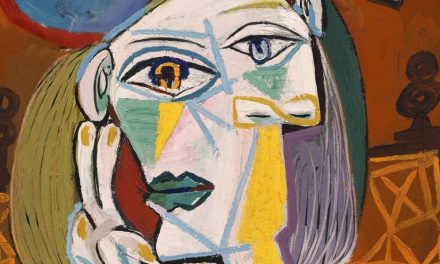

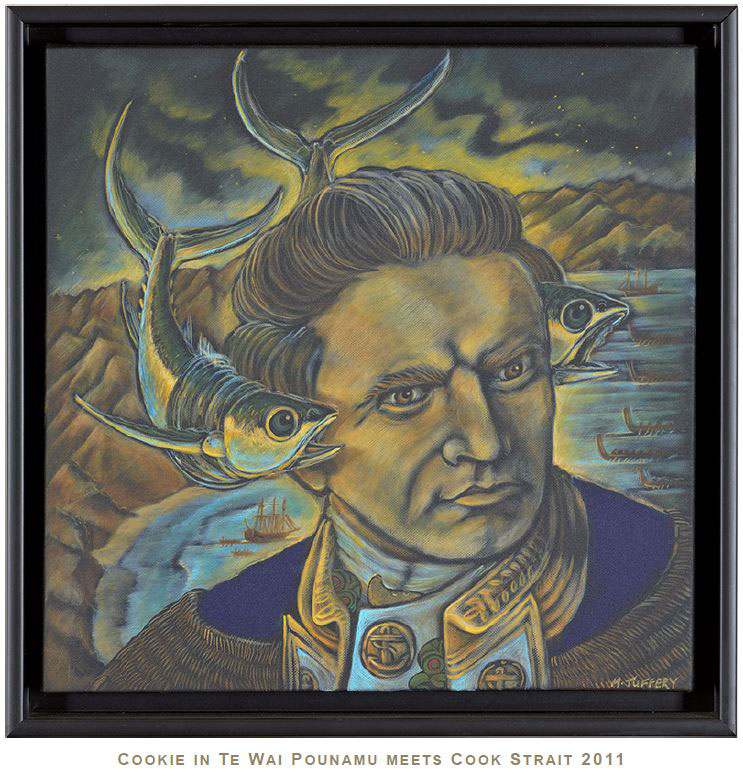

It starts with the technical minutae of his voyages: ships plans, models and, then artefacts and items he acquired, records and logs they kept, the details of his demise and finally what happened next: the masses of memorabilia, tokens and souvenirs that have been created since his death, ranging from Eulogies written by Catherine the Great, through pulp novels, modern abstract art and even childrens’ books inspired by him.

You’re left with as complete an image as you can have. Especially when the subject is one with such baggage. Cook simultaneously a remarkable figure of exploration, a harbinger of some of the worst excesses of colonialism and a near mythic figure thanks to the nature of his death. One of the most surprising things to me was that, while Cook is a towering character to us, the botanist Joseph Banks (the subject of another of the library’s displays) was a much more famous figure in their own time.

This is the fun of the exhibition. It is fully aware of the difficulty of finding the ‘real’ Captain Cook and aims to give you as many tools as possible. To that end, it features the viewpoints that were often neglected in the past. For instance, while it features the expeditions observations of the native peoples and their artefacts (including the wonderful story of one tribe’s professional mourners) it also includes their voices and their stories.

This way, they’re transformed from the dehumanised curios they often became in the era into both a part of its story and its tellers. And the exhibition doesn’t just pay lip service to the idea. Elders from multiple tribes throughout the country and the region were contacted to tell their half of the story, and they greet you as you arrive. Their voices are woven right into it. One of the best parts of the exhibition is a touch screen of the language journals that were made at the time. You can select individual words and have an elder of the relevant tribe tell you about the word’s meaning to them. Sometimes it’s the same word, other times, their tribe has the word, but with an adjacent meaning, similar to the overlap between the European Romance or Germanic languages.

Ultimately, no matter which aspect of his story you’re interested in, there’s something for you. whether you’re interested in the methodology of sailing, the cultures Cook encountered, reflections on that process or how the myth grew up around the man, there’s a wealth of stuff to look at. I was lucky enough to get a tour, and my guide could barely cram even a brief version into an hour. It’s a very worthwhile trip.